OUR HISTORY

OUR FOUNDER - ROD PALM

Rod Palm has dedicated his life to researching and monitoring the marine environment of western Vancouver Island. Since founding Strawberry Isle Marine Research Society (SIMRS) in 1991, as a platform for monitoring Bigg’s Killer Whales, he has orchestrated a number of important studies focused on marine ecology. SIMRS operations first began in the historic Norvan - a North Vancouver ferry boat and later steam tug boat built in the early 1900’s. Rod and his family mounted the vessel on Strawberry Isle from which the Society got it’s name. Rod has an unrelenting passion for the ocean and the many organisms that inhabit it as well as a well-stocked collection of stories at sea. Read some of Rod’s Scuttlebutt stories dating back to 1992!

A FRIENDLY VISITOR - July 1992 by Rod Palm

On July 11, a visiting tourist, strolling the beach at Schooner Cove, came upon a rather rotund, fur bearing, air breathing, snorting, sand slinging ... “thing”. Parks Wardens were notified and identified the animal as a yearling elephant seal hauled out for its annual molt.

Elephant seals are rarely seen in our waters and have never hauled out to molt in the history of the park. Tipping the scales at over 4,000 lbs. (2,000 kg.), these are the largest pinnipeds (marine mammals with webbed feet) who visit the B.C. coast. Born on the Californian or Mexican shores in the winter they may, in the summer, forage as far north as Alaska. Recent studies have these guys diving as deep as 4,150' (1,265 m) in pursuit of ratfish, sharks, eels and squid, this makes them the deepest diving of all the pinnipeds. With the heavy sealing of the turn of the century, elephant seal numbers were down to a few hundred animals but protected breeding grounds have allowed their population to return to historic levels, over 100,000. The fact that they don’t regularly feed on any commercial fish species has saved them from the wrath of fisheries management and fishermen.

A ribbon boundary was put in place around the Schooner Cove elephant seal but turned out to be of limited value. People respected the area of privacy but the seal was of a much more sociable nature. He daily moved about the campground intriguing adults, fascinating kids and scaring dogs. As often as not, he would plunk himself down, for the night, in the exact place where a tenter would want to light a campfire. Most of his day was spent soaking up rays and applying sun screen, that is to say, hucking sand up on his back with his fore flippers. The method used to get sand on his face, was to drive his pointed nose into the sand, then a violent honk sent an eruption skyward to come raining down on his head.

When our friend initially hauled up on the beach, his skin had a crinkly appearance, almost scaly. As the days went by he started to look as though he had a bad case of mange then, finally, his velvety grey fur was obvious.

On the morning of July 27, the seal hauled himself down to the water and departed. It was felt that this being his first molt, he may come back to this same beach next year.

On the evening of Aug. 2, an elephant seal fitting the description of the Schooner Cove seal dragged himself up on the beach at Green Point to die of a gunshot wound to the head.

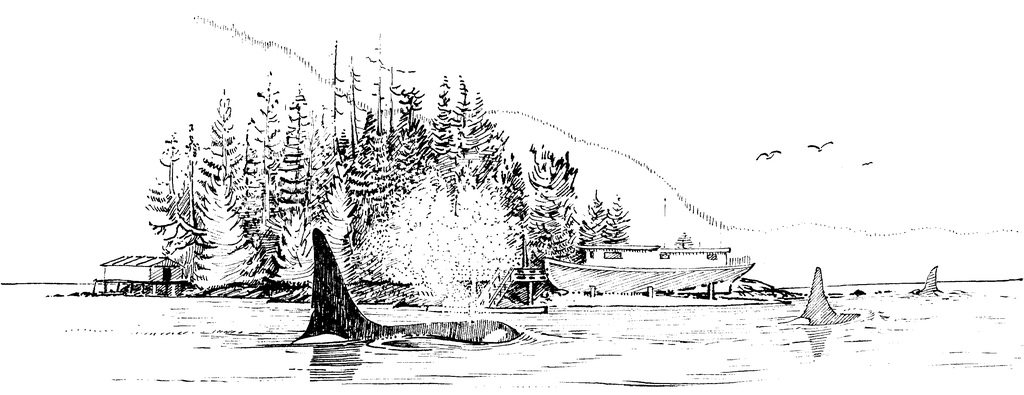

TRANSIENT KILLER WHALES in CLAYOQUOT SOUND 1994 by Rod Palm

Wow! What an exciting year for Kawkawin. Killer whales were in Clayoquot Sound on 52 days. This represents 15 transient pods containing 44 animals and four Northern Resident pods containing 28 plus animals. I should point out here that these resident visits are the most frequent we have recorded since the study began in 1991. This was likely related to the strong spring salmon run we had. The reason for the distinction, ‘resident’ - ‘transient’ is that these whales are actually evolving into two different species; they have not interbred in tens of thousands of years. Residents have blunter dorsal fins, more elaborate saddle patches, feed primarily on salmon and rarely wander from their specific territories except in the winter when they leave for places unknown. Transients travel in smaller pods (usually 5 or less), go wherever they please and do whatever they feel like. These guys like warm blood: seals, sea lions, dolphins, porpoise, sea birds and other whales. Last year in Alaska a pod of transients killed and ate a Moose that was swimming across a channel. We call transients the ‘motorcycle gang’ of the killer whales. On several days we were treated to three pods in separate locations in the Sound. That sounds great but it’s enough to turn your hair grey (explaining my present condition) when you’re trying to find out who’s who. Identification under these circumstances is becoming ever more efficient with the growing expertise between the whale watching skippers and their utilization of our Clayoquot Sound killer whale identification booklet.

There were several exciting encounters in 94', the first being performed by the Motley Crew. This pod contains the big bull U2, his mom, likely his aunt, a nine- year-old sibling (unknown sex) and his year and a half old sister Axle. In April these whales were heavily foraging for some species of fish close to the bottom on their way out of Father Charles Channel. As often happens after a good meal, the whales began an exuberant display of rolls, spy-hops, tail and fin slaps, upside down swimming and breaching. This performance carried on for over an hour. By this time they were out in front of Cox Bay. Now, who happens to be migrating up the coast minding their own business, but a mom and calf grey whale. The killer whales are with them in an instant. I must note here that although killer whales are known to attack and kill other whales, even their own species, our guys here on the coast have never been recorded partaking of this behavior. There has been ample opportunity; on several occasions we have watched with bated breath as orcas swam right through or past the grey whales in their summer feeding grounds. We often see very nervous greys trying to hide in the surf but our transients always passed them by without hesitation. Oh yes, on with the story. Mama grey scooped up her baby with one pectoral fin, rolled over on her back and arched up her stomach lifting her calf right out of the water. U2 lunged up on the side of the mother, reaching with gaping jaws for the baby. He did this several times then mother rolled over and dove, still holding onto the calf with her fins. All was quiet for a few minutes then the greys surfaced in Cox Bay and the orcas were back on course for Cox Point. This whole incident lasted but a few minutes.

It’s a cold afternoon in May. Motley Crew is traveling with Pandora, her son Kawatsi and daughter Eacott. They ran up the coast, through Tofino Harbour, up to the head of Tofino Inlet then back out and around the east side of Meares Island. Just as dusk was falling they unexpectedly all surfaced in very shallow water at Hankin Rock. One of the females pops up within a meter of the boat while both bulls surface in an explosion of water, fins, tails and erections. These guys are excited! The aggression here is unmistakable, I feel as though I’m locked into a contest of titans. It is getting dark and it’s started to rain and the whales are moving so fast that I am unable to distinguish who is who. Throw the hydrophone over the side and everyone is screaming at each other, I have to turn the speaker down. The bulls are slamming away at each other with their mighty tails while rolling and thrashing in a watery battle royal. Someone is hot for the other’s mother and he doesn’t like it. After over half an hour of this, the whales start slowly moving away from the rock but continue to vocalize and the mood has changed to one of exuberant frolicking. It is now dark but I can still follow the whales by the great white waves that burst up as they breach. As things start to settle down I realize that without rain gear I‘m getting dangerously cold so It’s time to leave. We will be watching these two pods very closely next year in hopes of a new calf. New births among our transients don’t happen very often, there were none in 94'.

August, Wakana and Rainny are pillaging their way down the coast. First stop, Lennard Island to unceremonious scoop up a couple of Harbour Seals for lunch, then a snoop around the Gowland Rock seal rookery and on to Portland Point.

I see an unawares bull Stellar Sea Lion right in the line of travel, oh oh. The orcas submerge and moments later the one ton sea lion is thrown through the water by a powerful tail. They are unmerciful; the hapless animal is smacked around by one orca after the other. For an instant, the sea lion is alone on the surface frantically swinging his head as he looks in all directions both above and below the water. Rainny bursts into the air and comes down on top of the sea lion in an explosive splash. The whale watching vessel “Chinook Key” has just arrived on the scene and skipper Earl Thomas finds himself with one battered sea lion trying to drag himself up onto the boat. It takes several minutes before the sea lion is in a position where Earl can safely throw the boat in reverse and get clear. Several more minutes of battering and they are gone, leaving one very bruised and bewildered sea lion behind.

September, what a month. On the first, Pachena is foraging in Tofino Inlet with her son Nitinat and two year old infant Vargas. Vargas takes an interest in a Marbled Murrelet and the race is on, the murrelet dives and surfaces about ten meters away with Vargas hot on its tail. The bird is bouncing across the surface trying to fly away but Vargas scoops it out of the air on the fourth bounce. This is the first recording anywhere of a killer whale getting a Marbled Murrelet.

September 9, Wakana is back with son Rainny and four other whales with quite unimpressive ID numbers. They have been hunting their way down the coast then split up at Schooner Cove. True to form, Wakana and Rainny angle offshore to check out a shallow reef off Long Beach. What now? The Orcas are in a frenzy, dashing about in very tight maneuvers. A harbour porpoise, they have him. Next, is not for the faint of heart. On of the Orcas gets a hold of the porpoise’s tail and literally whiplashes him out of his skin. You must appreciate that for a short time, the unfortunate porpoise would remain alive. The carcass itself was not consumed. I believe the reason for this waste is that the orcas are likely full from previous feeding and are just after the calorie rich blubber layer under the skin. Just a little chum is after a big meal.

September 12 was Clayoquot Day for Killer Whales. Never have so many transient pods gotten together. My first call was from the whale watch vessel “Sun Raven”, skipper Don Travis is with a half dozen orcas and others are heading in from the west. When I arrive, yet more whales are on the scene, I see Motley Crew, Kawatsi and her family, Wakana and Rainny, Ted’s and Mike’s pods, Langara’s pod and several whales who only go by designated numbers. It’s “Party Time”, whales are breaching, spy-hopping, tail slapping and performing all sorts of hijinks. The vocalizing is a mad cacophony of everyone trying to talk at the same time (John Ford of the Vancouver Aquarium says it will take him several weeks to decipher the tape). This behavior caries on for over two hours before the whales slowly start moving offshore, still cavorting. Oh look, late arrivals, Flores and her son Pender, just in time for the big race. The whales have been slowly picking up speed as move into position in a half mile long line of dorsal fins. They start moving faster and yet faster till they are slicing a long white line of churning water through the placid Ocean. The mood is intense, whales are passing each other, some are falling back and they are in the air almost as much as they are in the water. Some one viewing this scene might be alarmed to see a wild haired human charging along with the rampaging whales, hooting, hollering and gesticulating as though possessed. The race lasted for over half an hour with the whales attaining speeds of close to twenty knots. As they slowed down, the individual pods started breaking away and heading further out to sea. Flores and Pender are the last to leave, also heading offshore. There is the euphoric tingle in the air of coming down from a natural high. I follow Pender and son as they take up a relaxed pace on their offshore trek. When I loose them in the dark, a glance at the G.P.S. shows we are 17 miles offshore from Wilf Rocks. It’s time to call it a day.

This research will be funded in 95' by the Tofino Whale Watching Industry along with the Clayoquot Biosphere Project who gave financial support in 94'. My thanks to all.

Strawberry Isle Research Scuttlebutt by Rod Palm - October 2004

The year is 1909. Father Moser from the Christie Indian Residential School (Kakawis) is at Echachis at low tide looking towards Mount Colnet. With his handy-dandy tripod mounted, 50mm fixed lens, glass plate negative camera, he is making an image of what may be the last Humpback whale (iihtoop) taken in the traditional first nations fashion. Ya-sshin Jack (Alice Jack’s grandfather) killed this whale and they towed it to Echachis in 1909.

The harpoon used would not have been constructed in the old manner of bone, mussel shell, spruce root and yew wood. At this time they were using steel harpoons with a pivoting barb that toggled inside the whale. This devise had a line fixed to it and a wooden socketed shaft that released once the strike had been made. Sealskin bladders were likely still used as floatation drag for tiring the animal. The killing stroke would have been made with a meter long sharpened steel shaft without barbs. Though there are no obvious canoes (chupits) in the image, the skid marks where they were dragged up above the high tide are clearly visible on the beach. The stern of one chupits can be seen still in the water behind the whales head.

The large pectoral wings of the whale have been lashed tightly to the animal’s side to cut down on drag and the unnaturally closed mouth tells us that it was secured shut with the tow line being fixed through the blubber in the animal’s snout. The European fashion was to cut the flukes off and tow the animal by the tail. I have tried towing a dead whale using both methods. Towing head first works fine at slow speeds as would be the case using several chupits. When you put the pedal to the metal with a power boat, the animal dives under water creating tremendous drag. Even towing from the tail, an 8 meter Killer Whale (Kawkawin) took us 11 hours from 10 miles off Hot Springs to Strawberry Isle (see Scuttle Butt Oct. ‘97).

The man holding a line in the left foreground appears to be waiting for a man at the whale’s tail to fasten a line. I believe that the intent here is to pull the animal higher up the beach on the next high tide. This makes sense as the whales head sits much lower in the water so the rest of the body can get further up the beach. The line is too thin to have been used as a tow line.

A man standing between the whale’s tail and the people sitting on the beach appears to me hold a long curved flencing knife in anticipation of the butchering job in front of him.

In the old days, the tribe would get together and haul on a stout lines fastened to the opposite side of the whales body thus rolling the carcass onto its stomach. This made for easier access to all of the meat and blubber. There is no evidence of this preparation being made in the photo.

Echachis was the place to bring a whale as it has a pea gravel beach, much nicer than a sand beach as beach picnic people will attest.